AZZEDINE ALAÏA: VISIBLE BODIES

BY RICCARDO CONTI

Too soon. Too late. The conception of time in fashion is never linear. It is characterized by repetitions and syncopes, deviations and delays. At times real revolutions remain invisible at length.

Azzedine Aläia is an example that most perfectly represents the complex relationship between being a stylist and the temporal phenomenon that fashion describes. If the height of this stylist's splendor can at first be identified as having occurred between the 1980s and the early 1990s, his influence has since been so pervasive it has almost become invisible. Indeed, still today, whenever we notice, while looking at the catwalk, a tight-fitting dress, a leather jacket with a miniskirt and zippers that wrap around the body, we intuit that there, in all its purity, is a sign of Azzedine Aläia.

In 2022 Thomas Demand's solo show Model Studies opened at Matthew Marks gallery in Los Angeles. The exhibition consisted in four large-scale photos taken by the German artist in Alaïa's archive after his passing. The foundation had initially sent him to take pictures of the stylist's desk, but Demand was instead struck by the paper patterns hanging in the workshops and in particular by the ones preliminary to the making of leather garments.

The paper patterns and tracing paper in Demand's shots are the remains of Alaïa's creative process, and actually served as operative tools that he used to design clothing. In the artist's photographs the paper shapes become abstract compositions in warm hues that the viewer would find hard to relate back to the imaginary of Alaïa's radical elegance.

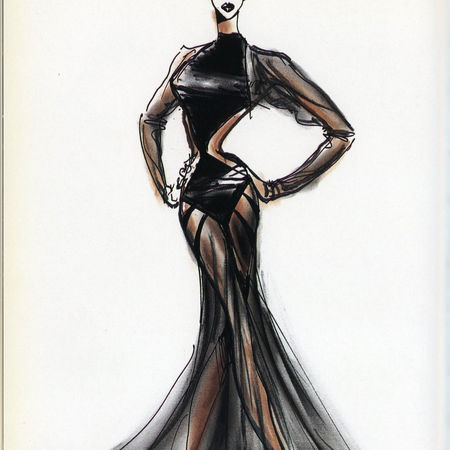

And yet, while the images taken by famous artists that alongside Alaïa consolidated his legend, revealing his final manifestation, the dress that is worn and 'embodied' (especially in the photos by Peter Lindbergh), Demand managed to delve into the conceptual origin of Alaïa's process, capturing its idealistic significance. The stylist's sign is present in the cut-outs, in the designs, but at the same time the intention of those forms is, at first glance, absent: the viewer cannot glimpse an anatomical element and assume that the sinuous shape of a body will be hosted amidst the composition of those two-dimensional elements. Rather, there is a feeling this is all a plan for something greater to come.

The literature and stories that accompany the figure of Alaïa often linger on questions linked to the artisan's pre-eminence, to the legend (which is also true) of a nearly Platonic form of the haute couture that the stylist succeeded in bestowing on his creations. If one must come to terms with this vision, then they should fully understand that this result was achieved via the perfect application and translation of physical and conceptual models.

Around 1914 Marcel Duchamp made a truly amazing work. Titled 3 Standard Stoppages it consisted of a wooden box containing three oddly shaped 'rulers,' curved, irregular, and unsuited, obviously, to the purpose of any standard measurement. To achieve these shapes Duchamp dropped three one-meter-long threads from the height of one meter onto three canvas strips. The threads were then adhered to the canvases, preserving the random curves they had assumed upon landing. Cut along the profiles of each fallen thread, the canvases served as templates for three draftsman's straightedges, a very personal Dada standard that Duchamp also used in other works like Réseaux des stoppages (Network of Stoppages) (1914). Akin to Duchamp's work, the curved models crossed by dotted lines in Alaïa's workshop are like a ruler that gives the bodies a shape, one that is made up of proportions and ratios and is not universal like a metric measurement, but is rather a measurement that corresponds to an ideal, unique anthropometry belonging to the stylist and to him alone.

It is always fascinating to see how a paper model made up of disassembled elements is the starting point that then leads to that final effect, to the apparition before our eyes of a finished, worn outfit. Alaïa knew how fundamental this passage was, and it is a well-known fact that he made all of his patterns personally. After drawing them and cutting them out, an assistant in his atelier would translate them into various dimensions; however, the first original model of a jacket or a dress was the result of work that he himself carried out, crafted from a prototype and an example of how an item of clothing can be constructed: "First, I have to work on the fabric. I have to cut it, think about the form, drape it over the bust, ponder it."

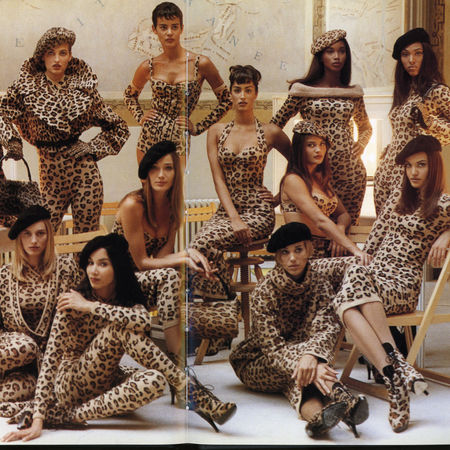

Contrary to many of his historical masters, to Christian Dior and to Guy Laroche, Alaïa's designs interacted directly with the anatomy. What Alaïa evoked during each of his shows was this crucial dynamic in clothing (whether it be haute couture or prêt-à-porter) as the alignment of the skin and the body's anatomy in the act of wearing it. Among the many examples, there are two specific ones that prove the extent to which the features of the body match those of the dress: the first of these is dated to 1987, of which a copy is preserved at the Kyoto Costume Institute. A 'simple' jersey wool dress, it both clothes and reveals the body, inventing new forms from the simple interaction between complex sewing and the anatomy. The other comes from the 1994 Spring/Summer collection and is now at the MET; made of acetate, rayon, nylon, Spandez, and metal, it is a reflection of master couturier Charles James's influence on Alaïa. The English designer's Sirène (1951-52) informed Alaïa's design, which would seem to be a negative of James's creation. Here the alternating bands of white and black knit reveal the shape of the figure, and echo the effect created by James's precise tucks. The black sections consist of houpette, a fabric developed by Alaïa based on short tufts of nylon resembling swan's down.

In both examples Alaïa's knitwear gently sculpts the body by creating various tensions in precise areas, but it ultimately relies on the wearer's body for structural support, underscoring beauty without in any way obstructing movement.

The clothed body is no longer entirely real; it becomes a screen of transformation, a way to talk without a verbal language. Even though its poses – like Erté's alphabet – become a new aesthetic code, Alaïa projects a profound sense of stability, a centering: by putting forward an attitude or a movement, the stylist can transform life and render the model's expression through the outfit. Alaïa had many beloved mannequins, from Bettina Graziani to Naomi Campbell, and that word, which signifies "model" in French, derives from the Ancient Dutch mannekijn, meaning "small man." Homunculus (Latin for "little person") was also a term used by alchemists to allude to the realization of the perfect human being.

In the words of Jean-Luc Nancy in Corpus (1992): "A body, first of all, is displayed as its photo-graphy (the spacing of a clarity). Only this, to begin with, does justice to a body, to its evidence. Beyond the body there is no evidence – clear and distinct as Descartes would have it be. Bodies are evident – and that is why all justness and justice start and end with these. Injustice is the mixing, breaking, crushing, and stifling of bodies, making them indistinct." Alaïa knew how to make this distinction like few others, he knew how to give identity back to bodies.

The outfit invites the person wearing it to become a bit like those mannequins. Simply by donning it, its true task is to help us to identify our optimal personalities. For us, finding the right fashion is a long path to becoming a slightly better version of ourselves, and that is also why for Azzedine Alaïa the time of fashion was of no importance.

Gallery